Introduction

In automated warehouses and industrial production lines, the performance limits of stacking robots are often not caused by control algorithms—but by the vertical motion system itself.

Many projects only realize this late in the process.

Unstable stacking, positioning drift under heavy load, increasing downtime after months of operation—these issues frequently trace back to one critical component: the lifting column.

As stacking heights increase, payloads become heavier, and safety expectations rise in the US and European markets, lifting columns are no longer optional mechanical elements. They have become structural, load-bearing cores that directly determine the reliability and service life of stacking robots.

In this article, we take a practical, engineering-driven look at lifting column applications for stacking robots. From real-world use cases to key selection parameters and compliance considerations, this guide is designed to help engineers and procurement teams make informed decisions when designing or sourcing stacking robot systems in 2025. If you are planning, upgrading, or sourcing vertical motion solutions for industrial stacking applications, this article will give you the clarity you need—before costly design changes happen.

To understand why the lifting column plays such a critical role, we first need to look at what a stacking robot really does—and where its structural limits come from.

What Is a Stacking Robot? And Why Vertical Motion is the Core Structure?

In industrial automation systems, a stacking robot is not just a “robot arm that stacks boxes.” From my experience working with automation projects, it plays a system-level role: it determines throughput, space utilization, and operational safety at the same time.

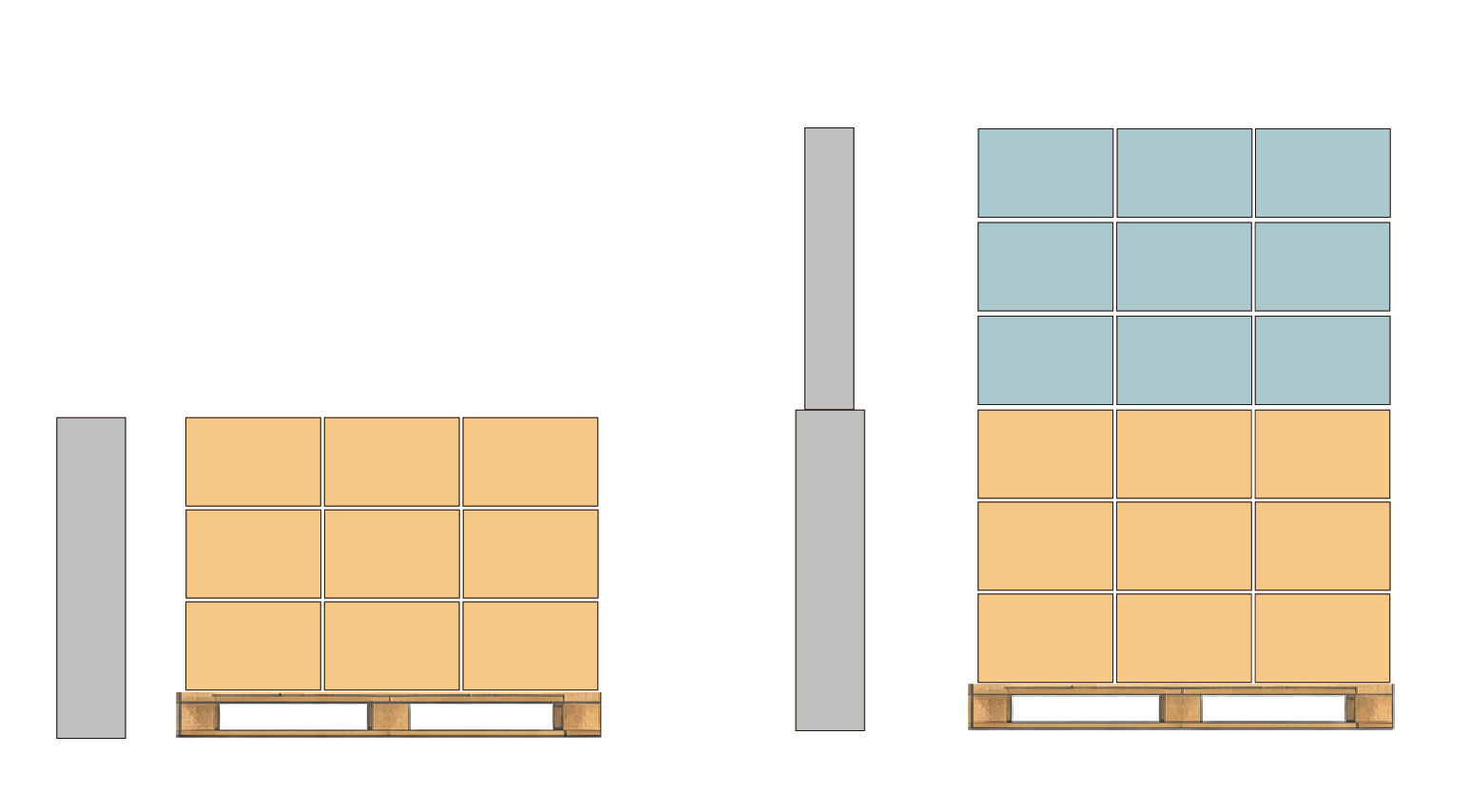

You’ll typically find stacking robots in automated warehouses, logistics centers, palletizing cells, and end-of-line production lines. Their job sounds simple—pick, lift, and stack—but the real complexity lies in the vertical motion.

Here’s the key point many teams underestimate: vertical movement defines the upper limits of a stacking system. Stack height, cycle time, and load stability are all governed by how reliably the robot can move along its Z-axis. Increase the height, add more payload, or push faster cycles—and weaknesses in the vertical structure show up immediately.

I’ve seen cases where a minor Z-axis issue caused a major system failure. A small amount of flex or positioning drift in the vertical structure gets amplified at the gripper level, leading to misaligned pallets, vibration, or even emergency stops. This is why Z-axis failures often have a disproportionate impact on overall reliability.

Ultimately, the vertical structure becomes the bottleneck because it must do everything at once: carry load, resist side forces, maintain precision, and operate safely over thousands of cycles. Get it right, and the whole stacking system runs smoothly. Get it wrong, and no control algorithm can fully compensate.

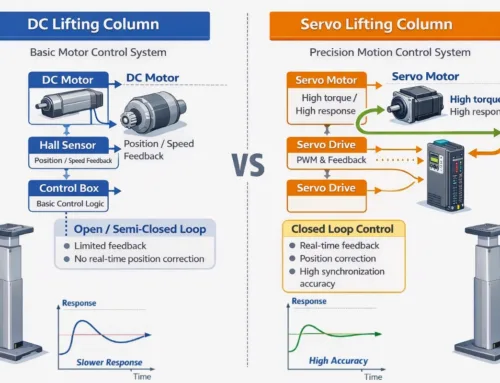

Why Are More Stacking Robots Using Lifting Columns Instead of Pneumatic Cylinders or Lead Screws?

This is a question I hear a lot from engineers during early project discussions—and it’s a fair one. Pneumatic cylinders and lead screws have been used in stacking systems for years. So why the shift?

From real-world experience, pneumatic systems struggle with precision and consistency. Air is compressible by nature. Under changing loads, positioning accuracy fluctuates, and energy consumption stays high because compressors run continuously. In one warehouse project I reviewed, compressed air accounted for nearly 30% of the system’s total energy cost—yet vertical positioning was still unstable at higher stack levels.

Lead screw solutions solve some precision issues, but they introduce new risks. As stroke length and payload increase, buckling, wear, and backlash become real concerns. I’ve seen long-stroke screw systems perform well on paper, only to show vibration and alignment problems after a few months of operation.

Lifting columns approach the problem differently. They are designed as load-bearing structures, not just motion components. Their enclosed profiles offer higher stiffness and better resistance to bending moments—critical in tall stacking applications.

Safety is another decisive factor. Integrated anti-drop mechanisms, mechanical locking, and power-off protection are far easier to implement with lifting columns than with air cylinders or exposed screw systems.

When you look at total cost of ownership, the picture becomes clear. Fewer failures, lower maintenance, and predictable performance over years—not months—are why lifting columns are becoming the preferred choice in modern stacking robots.

5 Key Lifting Column Selection Parameters for Stacking Robots

When it comes to stacking robots, I always tell engineers this: most failures don’t come from choosing the “wrong brand,” but from choosing the wrong parameters.

1. Load

Many teams only look at rated static load, but in real operation, dynamic load matters more. Acceleration, deceleration, and off-center payloads can easily increase effective load by 20–40%. If that margin isn’t considered early, problems show up fast.

2. Stroke length

It’s tempting to size the lifting column exactly to the maximum stacking height, but that leaves no room for safety clearance, tooling offsets, or future changes. A small buffer in stroke length often prevents major redesigns later.

3. Speed

Speed is another trade-off. Higher lifting speed improves throughput, but it also increases vibration and structural stress. In one project I reviewed, reducing vertical speed by just 15% significantly improved stacking stability without hurting overall cycle time.

4. Positioning Accuracy

Positioning accuracy and repeatability are often misunderstood. High accuracy matters, but repeatability is what keeps pallets aligned over thousands of cycles. For stacking robots, repeatability usually matters more than absolute position.

5. Duty cycle.

A lifting column that looks perfect on paper may overheat or wear prematurely if it’s not designed for continuous operation. In high-throughput stacking systems, duty cycle is often the silent bottleneck that defines long-term reliability.

What Procurement Teams Should Look for When Selecting a Lifting Column Supplier for Stacking Robots

From a procurement perspective, choosing a lifting column supplier is not just about unit price—it’s about risk control over the entire project lifecycle.

The first decision is standard models vs. custom solutions. Standard lifting columns may work for generic applications, but stacking robots often involve unique loads, heights, or mounting constraints. In my experience, a semi-custom or fully custom solution early on is usually cheaper than forcing a standard product into an unsuitable design later.

Next is the OEM vs. ODM cooperation model. OEM suppliers deliver to your drawings; ODM partners contribute engineering input. For complex stacking systems, suppliers who can challenge assumptions and suggest structural improvements add real value.

Sample and small-batch lead time is another critical factor. A supplier that takes 10–12 weeks just to deliver a prototype can easily delay the entire automation project. Fast sampling often reflects strong internal engineering and manufacturing capability.

Documentation should never be an afterthought. Complete drawings, load curves, duty cycle data, and certifications are essential—not only for engineers, but also for compliance reviews in the US and EU markets.

Finally, look beyond the first order. Long-term supply stability and technical support matter far more than a slightly lower initial quote. In stacking robots, continuity and support are what keep systems running reliably for years.

Common Lifting Column Selection Mistakes in Stacking Projects

In real projects, most lifting column problems don’t appear on day one—they surface months later, when changes are expensive. I’ve seen this pattern repeat across many stacking robot deployments.

The most common mistake is underestimating load. Engineers often calculate only the payload weight, forgetting acceleration forces and off-center loading. The result is gradual structural deformation or premature wear that quietly reduces system accuracy.

Another frequent issue is ignoring duty cycle. A lifting column may handle the load perfectly, yet overheat after hours of continuous operation. In high-throughput stacking lines, this leads to thermal shutdowns that are hard to diagnose and even harder to explain to operations teams.

Side loads are also widely underestimated. Pallets are rarely perfectly centered, and even small lateral forces can multiply bending stress at full extension. Without sufficient column stiffness, vibration and alignment errors become inevitable.

Control mismatch is another trap. Using high-precision servo systems in low-accuracy applications wastes budget, while under-specifying control in precision stacking leads to inconsistent results.

The most costly mistake, however, is changing the lifting solution late in the design phase. At that point, mechanical redesign, new validation, and delayed commissioning quickly turn a small decision into a major cost risk.

Conclusion

In stacking robot systems, a lifting column is not just another actuator—it is a core structural element that directly determines stability, safety, and long-term service life.

Whether you’re an engineer designing the system architecture or a procurement professional evaluating suppliers, lifting column selection must be based on real operating conditions, including load dynamics, duty cycle, and regulatory requirements. Skipping these fundamentals often leads to performance compromises that no control algorithm can fully fix.

From real project experience, one pattern is clear: the earlier the lifting column strategy is defined in the design phase, the lower the risk of costly rework later. Late-stage changes almost always mean structural redesign, delayed commissioning, and higher overall cost.

If you’re planning or upgrading a stacking robot for the US or European market, a well-matched lifting column solution will usually deliver more reliability and long-term value than adding complexity to software or controls. Getting the vertical structure right is often the smartest engineering decision you can make.